How To Save The Web

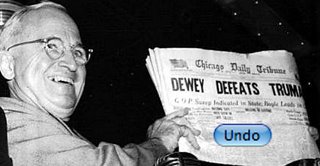

A strange as it may sound, public record does not exist on the internet. Consider this: it would be impossible for, say, the New York Times to change something it printed in 1997 -- there are hardcopies all over the world. But for nytimes.com it's as simple as a mouse click. So the internet we have today is public but it's not really a record. Healthy public record is the foundation of a free and literate society.

I propose that a loosely-connected network of independent archives, running on personal computers, under the care of self-interested individuals, and sharing common data formats, can in time self-assemble into something that fits the bill.

How we got here

For historical and technical reasons, stuff published on the web lives primarily on servers controlled by the original publisher. It is "distributed" at the time it is asked for, one copy at a time, and that copy is usually discarded. This means that if the original publisher goes away the authoritative source goes too. It also means the publisher, be it a company, government agency, small club or individual, gets to choose how the data is accessed now and in the future. This new power has become very tempting [0]. The mainstream is slowly realizing that stuff frequently disappears by accident and by design [1]:

For historical and technical reasons, stuff published on the web lives primarily on servers controlled by the original publisher. It is "distributed" at the time it is asked for, one copy at a time, and that copy is usually discarded. This means that if the original publisher goes away the authoritative source goes too. It also means the publisher, be it a company, government agency, small club or individual, gets to choose how the data is accessed now and in the future. This new power has become very tempting [0]. The mainstream is slowly realizing that stuff frequently disappears by accident and by design [1]:

- sports.yahoo.com "...a New York computer security expert who found official Chinese documents that list He's age as 14 years and 220 days... The spreadsheets were taken down off the site recently and He's name had been removed..."

- www.talkingpointsmemo.com "When we went to the page for the photograph of President Bush and Abramoff, the page in question had disappeared from the site..."

- www.nytimes.com ...Said videos were posted, then mysteriously disappeared from the Edwards Web site, with officials muttering something about campaign finance rules...

- perezhilton.com "Pinksky's photo disappeared from the hospital's site on Friday, as the scandal story started to get more legs..."

Wouldn't people notice if things went away?

Most often they don't, and if they do notice, so what? Revisionism and neglect is low-risk. "Orphan" works are sometimes rescued by their fans. But it's easy to forget that these cases are the exception. Intelligent, influential people say things like this: "Once the Internet knows something, it never forgets. This material just doesn't disappear from the Internet if it's sufficiently interesting." [2]

There are serious problems with this idea. The Rosetta Stone didn't survive thousands of years in the desert because of some intrinsic cultural value. It survived because it's made of stone. The UNIX crowd learned this lesson a few years ago to their lasting regret: there are no digital copies of the first four versions of UNIX, only some printouts.[3]

Worse is the implication is that if something is not "sufficiently interesting", if it's not part of the story a society wants to tell about itself, it's worthless. The future disagrees about what is and is not important, and why. That's the defining characteristic of the future. No one today cares what the Rosetta Stone actually says [4], yet it is more important to us (as the key to hieroglyphics) than it was to the society that made it.

The current situation

The current situation in archives is much like the web: uncoordinated, conflicting, changing. The most widespread problem is a paradoxical attitude: most people understand that a centralized web would be unsustainable, but few seem to carry that logic over to archiving.

There are a few public archives. Many national libraries have set up consortia to study the problem. There are search engine caches like Google's. There is the remarkable and far-sighted archive.org. All of them are welcome --in this game, the more the merrier-- but I believe they have various flaws. Google's cache exists for Google's purposes, and is not designed for the long term [5]. The LOCKSS project [6] is commendable in sprit and clever in design, but access to it appears to be limited to select universities and libraries.

Archive.org has two handicaps. It's not actually possible for one organization to curate the web. Second, being a non-profit sitting target, they are forced to take down stuff they do save [7] [8]

In April 2004 The public editor of the The New York Times spelled out the paper's position in an article titled "Paper of Record? No Way, No Reason, No Thanks". He was speaking more against the obligation to print government notices than the idea of public record per se. But all through it he assumes that (a) someone else will do it, and (b) this information (not to mention copies of his newspaper) will always somehow be available to future historians. At the same time his newspaper was telling archive.org to remove nytimes.com from the collection [9].

What the Archive should be

- Decentralized & Redundant

Centralized is too expensive and too fragile. Redundancy increases the odds of survival.

- Long-Term

If it's not long-term there's not much point. Open, stable formats.

- Locally curated

There should be at least as many opinions about what should go into the archive as people using it.

- Public & Coherent

A cache is useless if no one can get to it. It should also contain only things that are already public.

- Verifiable

Whether by digital signatures or by comparing copies, or both, the archive must be resistant to tampering.

- Respectful of privacy

A lot can be revealed by someone's reading list, and the need to anonymize may conflict with the needs of tamper-proofing.

- Useful for User 0

It has to be useful even if you are the only user, otherwise there is much less incentive to use and contribute to it.

In short, we need something akin to the web itself: something that can grow without limit, yet does not require much centralized organization. It can be pulled into pieces and operate independently and merge back together. Once it reaches a certain size it, or at least the idea, will be impossible to kill.

In a sense the archive already exists, though in a low-energy state. Part of it lives in the browser cache of everyone's computer. These caches are not coherent, organized, searchable, or public. They also have a lot of stuff in there that is better left private. We have to work around that. But it's a start.

Dowser's approach

"The lost cannot be recovered; but let us save what remains: not by vaults and locks which fence them from the public eye and use in consigning them to the waste of time, but by such a multiplication of copies, as shall place them beyond the reach of accident."

Thomas Jefferson, 18 February 1791

Dowser is a program designed to run on a normal personal computer but operate exactly like a website. Its user interface is a fully-functioning website that is hosted by and only accessible to the local machine [10]. This website enables the user to add pages to their local archive, search many search engines at once (aka "metasearch"), search the local archive, add organizational tags, take notes, export and share, etc. It is not intended as a professional tool for research specialists, but as a helpmeet for "power users": journalists, students, writers, etc, who have a demonstrated need for powerful research tools but do not have the time or inclination to train on an academic-grade tool.

When a user adds a URL to the archive, Dowser will attempt to retrieve the content of this URL by itself, without reference to any private authentication or "cookies" held by the user. This helps to ensure that private data stays private. Optionally, Dowser will download linked images, videos and such, and any linked pages up to a user-defined "link depth". As time goes on, Dowser will occasionally "ping" the URLs it knows about to determine if they have changed. If so it will download the new copy and thus build up a change history.

The program will not allow the user to alter any data in his archive, though it is possible to delete anything. Since the formats are open and simple, a determined user can of course alter the archive data with other tools. We can't stop that, and should not try, but will be an interesting obstacle.

Pulling it together

So far we have only a local archive. What User 0 reads is saved and available only to User 0. So how do we share it worldwide without inviting spam or violating privacy or running afoul of the law, etc?

The seven qualities above are somewhat in conflict with each other. Privacy may conflict with the need to verify copies, decentralization conflicts with system performance conflicts with public access, etc. Centralized archives solve it by doing it all themselves and building up a reputation for trustworthiness. LOCKSS, which is a network of caching servers installed in many universities, depends on the mutual trust of those institutions for verification and limits public access to ward of lawsuits by copyright owners.

You and I aren't smart enough to solve the sharing problem. We should start small and listen to the users, to use the much greater imagination of the group. Make tools to allow User 0 to share with User 1, then User 2, etc, but make them orthogonal to the rest. Allow people to extend Dowser and use it in ways we don't expect.

The common feature of all of the current archiving schemes is that they are hard for a mere mortal to set up. In theory anyone can download archive.org's software and use it to build their own archive. In practice it's very tricky, and not worth the effort for most people to learn the ancillary skills like programming, systems administration, etc. You can't join LOCKSS without being a major university.

Archiving today is a luxury good: complex, balky, expensive, like cars before 1908. When something is a luxury and you want more of it, what do you do? You turn it into a commodity. Make the hard parts easy, do what you can for the harder parts, get something workable into the hands of a much larger group. They will take it from there.

Notes

- [0] Even for me. This is the second version of this essay. The first version is here:

http://carlos.bueno.org/save-the-web-v1.html - [1] It is, unfortunately, easy to find cases where data was disappeared. In 30 minutes I compiled this list of instances where something that went missing was important enough to be written about.

http://carlos.bueno.org/disappeared.html -

[2] "Paris Hilton's genitals have joined the undead - they will live forever, stalking the Internet until the last plug is pulled on the last network router."

http://craphound.com/cambridge_biz_lectures.txtFor a few weeks in 2007, the film industry fought a futile a battle to contain the dissemination of a short string of numbers.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/AACS_encryption_key_controversy -

[3] "Although most of the UNIX source code from before 5th Edition has disappeared, we are fortunate that paper copies of all the research editions still exist..."

http://minnie.tuhs.org/Seminars/Saving_Unix -

[4] The Rosetta Stone is a political ad, the equivalent of "your tax dinarae at work": "...he caused the canals which supplied water to that fortress to be dammed off, although the previous kings could not have done likewise, and much money was expended on them; he assigned a force of footsoldiers and horsemen to the mouths of those canals, in order to watch over them and to protect them, because of the [rising] of the water, which was great in Year 8..."

http://www.britishmuseum.org/explore/highlights/article_index/r/the_rosetta_stone_translation.aspx - [5] "Google takes a snapshot of each page examined as it crawls the web and caches these as a back-up in case the original page is unavailable... The Cached link will be missing for sites that have not been indexed, as well as for sites whose owners have requested we not cache their content."

http://www.google.com/intl/en/help/features_list.html#cached - [6] The LOCKSS project, "Lots Of Copies Keeps Stuff Safe"

http://www.lockss.org -

[7] People forget that curating the web was Yahoo's original failed idea.

As of this writing chillingeffects.org documents more than 90 "takedown" letters sent to archive.org alone.

http://www.chillingeffects.org/dmca512/notice.cgi?NoticeID=1899 -

[8] "The Internet Archive is not interested in offering access to Web sites or other Internet documents whose authors do not want their materials in the collection."

http://www.archive.org/about/exclude.php -

[9] "Paper of Record? No Way, No Reason, No Thanks", Daniel Orkent, public editor, The New York Times, 25 April 2004

http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9D02E1D8123AF936A15757C0A9629C8B63 There are about 3,400 pages for 2005, 1,800 for 2006, 550 for 2007, and only 30 pages for 2008 from nytimes.com in archive.org's public collection.

http://web.archive.org/web/*/www.nytimes.comI don't mean to pick on the NYT, but in the last few years they have gone to a lot of trouble to delete themselves.

- [10] This design is similar to Google's Desktop search application and several others. In addition to having seamless integration with external websites, this design avoids the tricky & tedious work of writing custom "plugins" for many combinations of operating system and web browser.