Cache is the new RAM

This is from a talk given at Defrag 2014.

This is from a talk given at Defrag 2014.

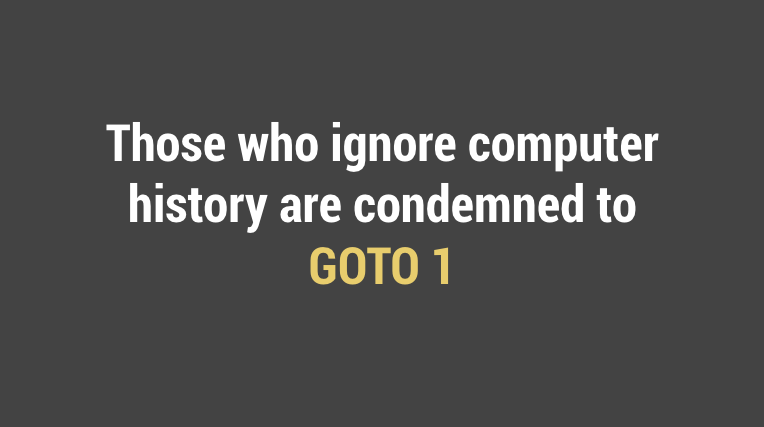

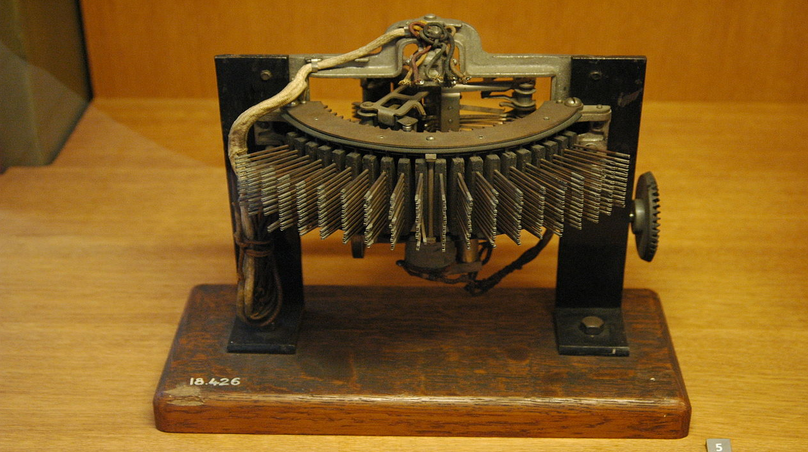

One of the (few) advantages of being in technology for a long time is that you get to see multiple tech cycles beginning to end. You get to see how breakthroughs actually propagate. If all you have seen is a part of the curve, it’s hard to extrapolate correctly. You either overshoot the short-term progress or undershoot the long. What’s surprising is not how quickly the facts on the ground change, but how slowly engineering practice changes in response. This is a Strowger switch, an automated way to connect phone circuits. It was invented in 1891.

In 1951, right on the cusp of digital switching, the typical central switching office was basically a super-sized version of the Victorian technology. There was a strowger switch for every digit of every phone call in progress.

From the perspective of the time, this was the highest of high technology. Of course from our perspective, it was the world’s largest Steampunk art installation.

It’s probably a mistake to feel superior about that. It’s been 65 years since the invention of the integrated circuit, but we still have billions of these guys around, whirring and clicking and breaking. It’s only now that we are on the cusp of the switch to fully solid-state computing.

The most exciting kinds of technological shifts are when a new model finally becomes feasible, or when an old restriction falls away. Both kinds are happening right now in our industry.

Distributed computing is becoming the dominant programming model throughout the entire software stack. The so-called “Central Processing Unit” is no longer central, or even a unit. It’s only one of many bugs crawling over a mountain of data. The database is the last holdout.

At the same time, the latency gap between RAM and hard drive storage is becoming irrelevant. For 30 years the central fact of database performance was the gigantic difference in the time it takes to access a random piece of data in RAM versus on a hard drive. It’s now feasible to skip all that heartache by placing your data entirely in RAM. It’s not as simple as that, of course. You can’t just take a btree, mmap it, and call it a day. There are a lot of implications to a truly memory-native design that have yet to be unwound.

These two trends are producing an entirely new way to think about, design, and build applications. So let’s talk about how we got here, how we’re doing, and hints about where the future will take us.

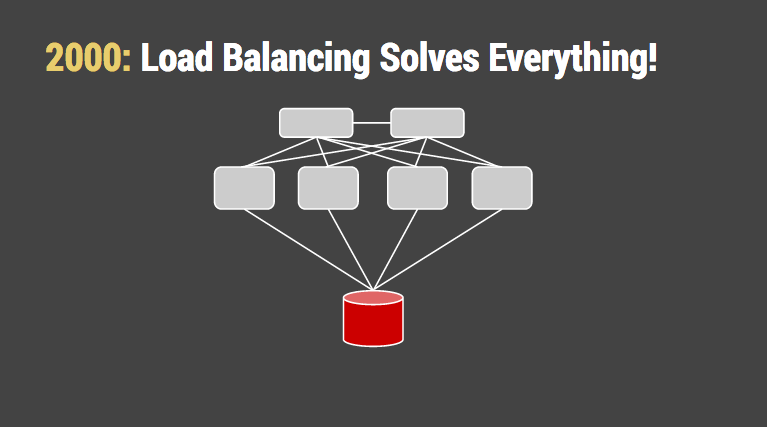

Back in the day, every component in the architecture diagram had a definite article attached to it. Each thing was a separate function: “the” database and “the” web server, characters in a one-room drama. Incidentally, this is where the term “the cloud” came from. A fluffy cloud was the standard symbol for an external WAN whose details you didn’t have to worry about.

Distributed computing hit the mainstream with the lowest-hanging fruit. Multiple identical application servers were hidden behind a “load balancer” which spread the work more or less evenly. Load-balancing only the stateless bits of the architecture sidestepped a lot of philosophical problems. As the system scaled up, those components outflanked and eventually surrounded “the” database. We told ourselves that it was normal to spend more on special database hardware with fast disks and a faster CPU, and it was only one machine anyway. The hardware vendors were happy to take our money.

Eventually, database replication became reasonable and we salved our consciences by adding a hot spare database. We then told ourselves there were no longer any single points of failure. It was even true — for a few minutes.

That hot spare was too tempting to leave sitting idle, of course. Once the business analysts realized they could run gigantic queries on live production data without touching production, the so-called “hot spare” became nearly as busy and mission-critical as the production copy. We told ourselves it would be fine because if the spare is ever needed we can just take it from them for the duration of the emergency. But that’s like saying you don’t really need to carry a spare tire because you can always steal one from another car.

Then Brad Fitzpatrick released memcached, a daemon that caches data in memory. (Hence the name.) It was amazingly pragmatic software, a simplified version of the distributed hash tables then in vogue in academia. It had lots of features: a form of replication, sharding, load balancing, simple math operators. We told ourselves that most of our load was reads, so why make the database thrash the disk running the same queries over and over again? All you needed was a bunch of small-calibre servers with tons of RAM, and of course the hardware vendors were happy to take our money.

And… maybe you have to write some cache invalidation code. That doesn’t sound too hard. Right?

To its credit, the memcached design took things a pretty long way. It replaced the random IO performance of a hard drive with the random IO performance of multiple banks of RAM. Even so, the database machine kept getting bigger and busier. We realized that caching cost at least as much RAM as the working set (otherwise it was ineffective), plus the nearly unbearable headache of cache consistency. But we told ourselves that was the cost of “web scale”.

More worrisome was that applications were getting more sophisticated and chattier. Multiple database writes were being performed on almost every hit. Writes, not reads, became the bottleneck. This is when we finally got serious about sharding the database. Facebook initially sharded its user data by university and got away with concepts like “The Harvard Database” for a surprisingly long time. Flickr is another good example. They hand-built a sharding system in PHP that split the database up by a hash of the user ID, in much the same way that memcached shards on the key. In their tech talks there are jolly hints about having to denormalize their tables and double-write objects such as comments, messages, and favorites.

But that’s a small price to pay for infinite scaling that solves everything ever. Right?

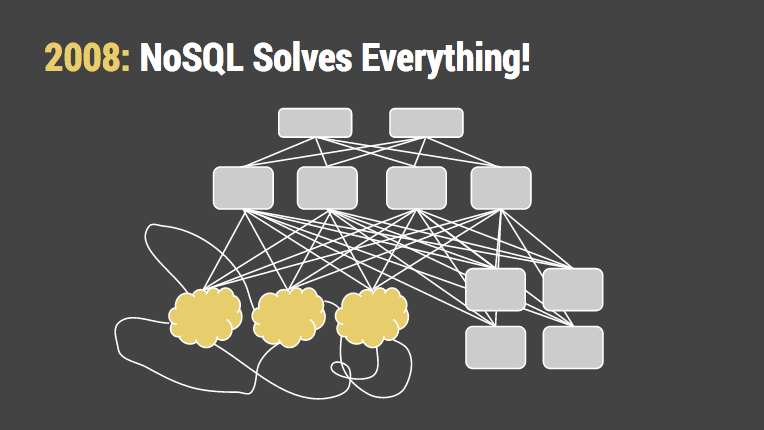

The problem with sharding a relational database by hand is that you no longer have a relational database. The API that orchestrates the sharding has in effect become your query language. Your operational headaches didn’t get better either; the pain of altering schemas across the fleet was actually worse.

This was the point at which a lot of people took a deep breath, catalogued all the limitations and warts of their chosen implementation of SQL … and for some reason decided to blame SQL. A flood of hipster NoSQL and refugee XML databases appeared, all promising the moon. They offered automatic sharding, flexible schemas, some replication… and not much else at first. But it was less painful than writing it yourself.

You know things are really desperate when “less painful than writing it yourself” is the main selling point.

Moving to NoSQL wasn’t worse than hand-sharding because we’d already given up any hope of using the usual client tools to manipulate and analyze our data. But it wasn’t much better either. What used to be a SQL query written by the business folks turned into hand-written reporting code maintained by the developers.

Remember that “hot spare” database we used to use for backups and analytics? It came back with a vengeance in the form of Hadoop filestores and Hive querying on top. Now this worked, and largely got the business folks off our backs. The biggest problem is the operational complexity of these systems. Like the Space Shuttle, they were sold as reliable and nearly maintenance-free but turn out to need a ton of hands-on attention. The second biggest problem is getting the data in and out; a lag time of one day (!) was considered pretty good. The third problem is that it manages to be I/O-bound on both network and disk at the same time. We told ourselves that was the price of graduating to BIG DATA.

Anyway, that’s how Google does it. Right?

As various NoSQL databases matured, a curious thing happened to their APIs: they started looking more like SQL. This is because SQL is a pretty direct implementation of relational set theory, and math is hard to fool.

To paraphrase Paul Graham’s unbearably smug comment about Lisp: once you add group by, filter, & join, you can no longer claim to have invented a new query language, only a new dialect of SQL. With worse syntax and no optimizer.

Because we had taken this strange detour away from SQL, crucial bits missing from most of the systems are a storage engine and query optimizer designed around relational set theory. Bolting that on later led to severe performance hits. For the ones that got it right (or papered it over by being resident in RAM) there were other bits missing like proper replication.

I know of one extremely successful web startup you’ve definitely heard of that uses four, count ‘em, FOUR separate NoSQL systems to cover the gaps.

It’s pretty clear that there’s no going back to “the” database and 10-million-nanosecond random seek times. Underneath the endless hype cycles in search of the One True Thing To Solve Everything Ever is an interesting pattern: a pain point relieved by a clever approach that comes with an new pain point.

So what’s the next complex gadget to add to this dog’s breakfast? Maybe the real trick is to make things simpler.

For instance, RAM: You have lots of RAM in the “database” machines, for caching and calculation. You also have lots of RAM in the Memcached machines. The sum of RAM in those systems should be at least equal to the size of your working data set. If it isn’t then you’ve under-bought. Also, I very much doubt that your caching layers are 100% efficient. I’ll bet money you have plenty of data that are cached and never read again before eviction. I’ll bet more money you don’t even track that. That doesn’t mean you’re a bad person. It means that caching is often more trouble than it’s worth.

A lot of the features each of these components provide seem to be composable and complementary to each other. If only they could be arranged better.

Once you take it as axioms that the system will be distributed and the data will always be solid-state, a curious thing happens: it all gets much simpler. The “temporary” memory data structures you’d normally only use during query invocation becomes the only structure there is. Random access is no longer a cardinal sin; it’s the normal course of business. You don’t have to worry about splitting pages, or rebalancing, or data locality.

This is a nice, simple architecture. Just as load balancers abstract away the application servers, SQL “aggregators” abstract away the greasy details of orchestrating the reading and writing of data. This keeps the guts of the data placement strategies behind a stable API, which allows both sides to make changes with less disruption.

So it’s all good now, right? We’re finally arrived at the happy place at the end of history. Right?

It’s a mistake to feel complacent about the state of the art of computing, no matter when you live. There’s always another bottleneck.

This is the AMD “Barcelona” chip, a relatively modern design. It has four cores but the majority of the surface is taken by the cache and I/O areas surrounding cores, like a giant parking lot around a WalMart. In the Pentium era cache was only about 15% of the die. The third, quieter, revolution in computing is how much faster the CPU has gotten relative to memory. There’s a reason all this expensive real estate is now reserved for cache.

The central fact of database performance used to be the latency gap between RAM and disk. At the moment we’re kidding ourselves that the latency gap between CPU cache and RAM isn’t exactly the same kind of problem. But it is.

And as much as we like to pretend that shared memory actually exists, it doesn’t. With lots of cores and lots of RAM, inevitably some cores will be closer to some parts of RAM.

When you get right down to it, a computer really does only two things: read symbols and write symbols. Performance is a function of how much data the computer must move around, and where it goes. The happiest possible case is a endless sequential stream of data that’s read once and dealt with quickly, never to be needed again. GPUs are a good example of this. But most interesting workloads aren’t like that.

Every random pointer that’s chased almost guarantees a cache miss. Every contention for the same area of memory (eg a write lock) causes huge coordination delay. Even if your CPU cache-hit rate was 99%, which it isn’t, time spent waiting on RAM would still dominate.

Or put it this way: if disk is the new tape, and RAM is the new disk, then the CPU cache is the new RAM. Locality still matters.

So what will solve this problem? It seems that there’s the same old fundamental conflicts: do we optimize for random access, or serial? Do we take the performance penalty on writes, or reads? Can we just sit tight and let the hardware catch up? Maybe memristors or other technology will make all of this irrelevant. Well, I want a pony, too.

The good news is that the gross physical architecture of distributed databases seems to be settling down. Data clients no longer need to deal with the guts and entrails of 4 or 5 separate subsystems. It’s not perfect yet; it’s not even mainstream yet. Breakthroughs take a while to propagate.

But if the next bottleneck really is memory locality, that means the rest of it has become mature. New innovations will tend to be in data structures and algorithms. There will be fewer sweeping architectural convulsions that promise to fix everything ever. If we’re lucky, the next 15 years will be about SQL databases quietly getting faster and more efficient while exposing the same API.

But then again, our industry has never been quiet.